University of Aberdeen — Social Sciences blog (1)

Category: Belonging

Pandemic information flows

Co-authored by the Brexit and Belonging team, and co-published across Media Effects Research and Brexit and Belonging.

In times of crisis when responsible action is required, we need clear and credible information. Our analysis shows that coronavirus news is produced in a concentrated network where news and information providers as well as the British public heavily rely on the BBC as a primary source.

With a number of running data initiatives at our disposal, including large-scale media mapping, passive metering of news browsing, and ethnographic fieldwork, we turned to explore some of the difficult questions related to the media coverage of Covid-19 in the UK and in particular how citizens manage the overabundance of information that is characteristic of the current “infodemic”.

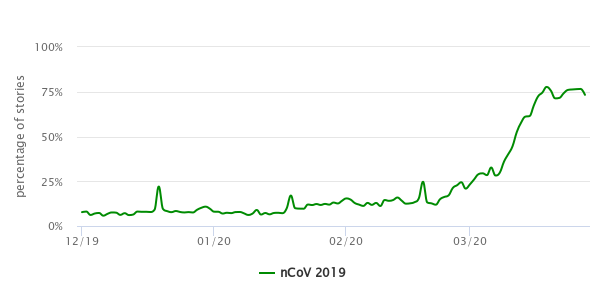

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the volume of stories mentioning coronavirus-related keywords* have grown exponentially, with the biggest spike between 8–19 March. By the end of March, three quarters of the entire online news landscape in the UK contained at least some mention of the virus.

Many fear that this abundance of information is anything but helpful as the public tries to navigate through an existential crisis, one that in the UK swiftly came after a news saturated Brexit crisis. Misinformation has been a pressing concern in both instances, with current coronavirus issues including the misrepresentation of preliminary scientific evidence, incorrect advice on causes, symptoms, and treatment.

To understand the scale of the problem, we turn to a coronavirus corpus of 215,952 news stories**. This contains some aggregate data on information flows we thus explore (1) the number of shares on Facebook aggregated per domain, and (2) the hyperlinks extracted from these stories. Then complementing this, we revisit (3) ethnographic fieldwork data from across the South West, North East and Midlands areas of the UK to gain additional insights into how citizens interact with, and make sense of, vast amounts of media coverage in practice.

In addition to this, we will also investigate the textual content of our stories to track coronavirus misinformation more specifically. We aim to blog the first results in the coming weeks.

(1) As the coronavirus pandemic unfolds, the British public increasingly turns to the BBC for information

Traditional sources of news such as broadcast news (BBC, Sky), and the more trusted partisan broadsheets such as the Telegraph and the Guardian are not able to keep up with the excess volume of news stories (see Y axis) generated by their online competitors (Yahoo), including the tabloid press (The Sun and Express). The volume of news produced, however, does not indicate whether the public finds it credible and of value. We find that over time, people were much more likely to share the stories, though small in volume, produced by the BBC. Social media sharing is an indication that the source is trusted and by this measure the BBC is far and above the most trusted source for Covid-19 information.

In that critical period of exponential growth in story volume in March 2020, the BBC emerged as the primary source of information. Our animation above shows this dynamic clearly as the BBC gradually shifts away from the rest of the sources around mid-March. By the end of the month, the BBC counted nearly three times as many shares on Facebook than its closest competitor out of 4,397 sources. These sources may be explored in detail by zooming into and hovering over the markers in the animation above.

The BBC’s strategic position has been noted by the UK government. PM Boris Johnson started his term in office with a boycott of BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme due to concerns about its impartiality. In addition, he accelerated attempts to shrink one of the most venerated news organisations around the globe by threatening to cut its primary source of funding by removing the license fee altogether.

The boycott has, however, ended during the pandemic and we would argue this was a wise and strategic decision. The BBC represents an opportunity for a shared news experience by the public. We think the public uses the BBC’s unmatched source credibility to navigate in times of crisis (and elections). Importantly the BBC can counteract any polarisation in news viewing experiences that is generated by social media.

Our findings resonate with a recent Ofcom survey reporting 82% of adults online using the BBC to find information about Covid-19.

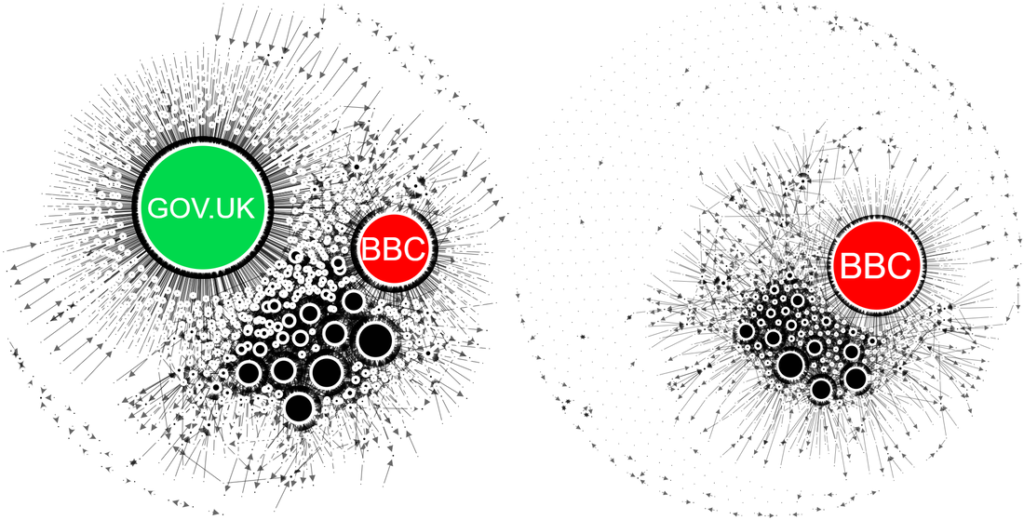

(2) News coverage of Covid-19 represents a concentrated news production network led by the BBC

We extracted all hyperlinks found in this corpus of news stories to draw a directed network representing the sources used to report on the coronavirus. For example, a news story from the Telegraph that contains a link to a BBC article is represented by the two “nodes” (BBC and Telegraph) and the linking edge: Telegraph ➡ BBC where the direction of the arrow indicates that the Telegraph is relying on the BBC as a source. We believe networks such as these offer a way of representing inter-media news production and agenda setting. In our example, the production of news in the Telegraph builds on the BBC. In our corpus of data, we found 10,251 such links between news sources.

Nodes represent 4,397 online news domains with coronavirus coverage. Node size represents the number of hyperlinks pointing to them from different domains.

Nodes (domains) are sized based on their in-degrees i.e. the number of links pointing to them from other sources.

As we would expect, the government web pages are the main source of information for other news outlets. But among news organisations, the BBC represents a main source of information in the news production environment. Our key point is, then, that the BBC provides an important source of credible information for individuals and is shared widely. Additionally, it is an important source for other news and information providers.

The entire Covid-19 coverage seems to be drawing on one main source namely the UK government’s communications. There are a large number news outlets and websites that connect to this node directly (many of them local news domains). Domains that have a traditional print format as well, however, seem to connect to this node indirectly via the BBC (the vast majority of them) but also via the more trusted and shared sites we already plotted above.

(3) A view from ethnographic research on Brexit and everyday media practices

The qualitative data comprise fieldwork notes from an ongoing ethnographic project as well as 180 interviews conducted in the South West, North East and Midlands areas of England. The fieldwork began in October 2018 and ended on January 31st 2020. The project explores questions of identity, belonging, and importantly for this blog, the role of media in “Brexit Britain”. Our focus is on the diverse types of knowledge that individuals mobilise to engage with media representations of Brexit. This process is contextualised within participant observation of individuals’ daily media practices with a focus on practices relating to news on Brexit and its outcomes.

One key theme emerging from our fieldwork across England is that the BBC was seen as a problematic source of information by both leavers and remainers. In this regard, people on both sides of the Brexit debate argued that the same BBC programmes were politically biased. For example, BBC1’s Question Time and Radio 4’s the Today Programme were thought by both leavers and remainers to be biased towards the side they did not support. Question Time was accused of having too many leavers or remainers on the panel and had was described as having ‘planted’ too many leavers or remainers in the audience. This marked mood of distrust of the BBC during the Brexit crisis renders the current return to the BBC as the most trusted source during this time of lockdown very significant.

In addition, it is worth highlighting that while people might be reading, sharing and discussing information on the internet during the lockdown, this does not necessarily mean they believe it whole heartedly. A key example here is that some ardent leavers we have spoken to did not straightforwardly believe the Brexit bus slogan “£350 million to the NHS”, rather they saw it as symbolic of the money that they thought the British government wasted on the EU.

It is also important to note that while it might appear that people are turning to the BBC during the pandemic, this statistic does not account for the ways in which people might also be reflexively managing their media consumption during this period of lockdown because they find the media emotionally distressing. For instance, we found that some people we spoke to about Brexit actively avoided media coverage on Brexit because the representation of the nation, national politics, disunity and governance was too upsetting. Likewise, similar (and hidden) patterns might well be at work now over the coronavirus coverage.

And finally there is something insightful to say from an ethnographic point of view about the idea that the social sharing of information is an indication of trust and source credibility. We found in our research on Brexit that people used social media e.g. Twitter, WhatsApp and Facebook to share news and views on Brexit. Facebook exchanges could at times cause tension and falling out amongst neighbours that were reproduced in everyday neighbourhood interactions. At the same time Facebook also united people who might not otherwise have known each other in communities of belonging and support around Brexit and this was the case especially for activists.

It would seem for Covid-19 that social media is being used as a way to connect people that might not have connected before via this medium because they are now having to socially distance and isolate from each other Facebook and other forms of social media are also being mobilised to share news, help and information that is locally relevant e.g. neighbourhood Facebook groups share news about which shops are offering home deliveries and how to volunteer in the community. Some forms of social media are also being used as sites to signal that help and care from those nearby is needed, and building new networks of social reliance and connection.

We aim to submit the underlying working paper to SocArXiv within the next few weeks. Please check back later for updates. In the meantime, feel free to cite this blog as source or contact us for more information.

* “coronavirus”, “covid”, “ncov”

** a near-complete coverage, but important exceptions apply. The Daily Mail has requested that Webhose API, our data source, do not crawl their content in our period of analysis. So far we know of no other major source missing.

Beyond the VOX pops

This article was co-authored by the Identity, Belonging and the Role of the Media in Brexit Britain research team, and first appeared on the LSE Brexit Blog.

The vox pops conducted by the national media give a simplistic impression of people’s opinions about Brexit. In our first blog post, we discuss how our early research findings probe more deeply into people’s experience of the topic and how it touches on their identities.

Recent Brexit coverage has been dominated by intra-party politics, parliamentary procedure and conjecture about Theresa May’s leadership. It has often sounded more like a sports match than a debate about the implications and features of May’s EU withdrawal plan. Updates on ‘the Brexit chaos’ in parliament are occasionally interrupted when the news media step outside of Westminster to see, hear and report on what people think.

Photo: Phil Gayton via a CC BY 2.0 licence.

Yet, even outside the Westminster bubble, these snapshots of what ‘ordinary’ people or the Great British Public think do not go beyond soundbites. Reporters often talk to people out shopping on the high street, in a snooker hall and so on, and often refer to their location, problematically, as a ‘left behind’ place. We hear: “We voted leave and so parliament should just get on with it”; “I used to be interested in politics, but not any more — I just turn it off when it comes onto the TV”. If we gave people more time to talk, what would they say about Brexit?

These vox pops are in stark contrast to the daily conversations that we are holding with people across England about Brexit and the Brexit process. We find that this Brexit moment provides a pathway to explore what we have come to think of as people’s Brexit narratives. These do include discussion on what is going on with the political process, but they are also opening up a space to explore something much more personal.

Our discussions are offering us insights into people’s place in and experience of the world. While people do discuss the rights and wrongs of the political moment, they also want to discuss with us how they are experiencing it, and situate their reactions to and experiences of Brexit in the wider context of their life-worlds. They draw on their biographies (what they are doing, plan to do and have done with their lives), including their place-based biographies (where they have lived and what it is like to live in their current city, town or village in England today).

Some people describe the politics of Brexit as having to do with their sense of social justice, fairness and equality. We are discussing what it means to be included and excluded in the world on the grounds of ethnicity, class, nationality and religion. We are exploring what social diversity and multiculturalism means, and what it feels like in England today. We are being given an insight into the impact that this Brexit moment has on people’s personal relationships, such as whom they feel they can talk to and about what, the impact of their views of the Brexit vote on their relationships with family members and at work, and their exchanges with friends, acquaintances and relatives in person, on email and via Facebook.

We also see insights into deep feelings of alienation and rejection from friends, loved ones, their community and society. What emerges from many of these conversations is a shared sense of concern from people right across the spectrum of Brexit views about a growing fragility in the norms of social civility — that the public space to ‘rub along’ with different views is threatened.

Also apparent is people’s sense of how they identify as ‘English’, ‘British’, ‘Welsh’, ‘Scottish’, as from Northumberland, Leicester or Devon, as ‘European’, as migrants, as mixed nationalities, as generational identities, as ‘white’, ‘black’, ‘mixed-race’, ‘Asian’ and as global citizens. We are working to understand what these identities mean for people. Other identities that crystallise around Brexit, such as ‘Leaver’ and ‘Remainer’, are also discussed at length. Participants seek to imagine the voting rationales of people with different Brexit identities to them. Such conversations deepen our understanding of people’s own identity by listening to how they imagine and construct ‘the Other’ in the Brexit debates.

A significant part of our work juxtaposes these Brexit narratives and ethnographic conversations with media narratives, and local media in particular. Our early impression is that local media plays an important role in giving voice to local actors and local concerns, rather than echoing the national discourse. Specifically, we found that a quarter to a third of political actors mentioned in our local news corpus (May 2016 — December 2018, on the websites of the Boston Standard, Chronicle Live, Devon Live and Leicester Mercury) are local actors such as MPs, or people speaking for local businesses and charities. While the most frequently mentioned politicians are national actors such as May and Jeremy Corbyn, the rest of the list is dominated by local politicians such as Catherine McKinnell and Chi Onwurah in Newcastle, or Ben Bradshaw in Devon.

Similarly, these headlines rarely echo those in the national broadsheets and tabloids. We built a news dashboard to track trending Brexit news in real-time based on social media virality, and observed differences between national and local outlets. Viral national news concerns the day-to-day developments in Brexit negotiations across and within partisan groups, and while local coverage does comment on these, separate stories are dedicated to local issues such as the car industry in Newcastle and Leicester or Flybe in Devon, or in general local perspectives that did not make the national news.

Beyond the soundbites presented by the national news media, discussions around Brexit involve wider claims about what people value and hold dear about their lives and the world. People make sense of ‘Brexit’ in relation to their own biographies, multiple identities, social and familial networks, and values. Brexit can also act as one prism through which individuals articulate their hopes and fears for the future. We argue that these are the everyday drivers that have been consistently written out of popular debate on the politics of Brexit.